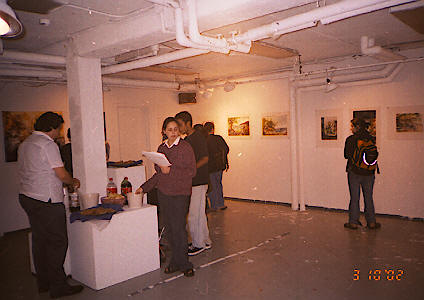

LEE Hui Ling's < Pictorial Journal >

Oct 3rd - Oct 6 th 2002 . 9am-9pm. Venue: A* Space

Sarah Lawrence College One Mead Way, Bronxville, New York, NY 10708

This exhibition is my pictorial journal. Paintings have a way of explaining things that photographs cannot. As much as I wish to accurately record what I see, the play of light has caused the images I see before my eyes as constantly moving; thus the picture that I capture with my mind and quavering brush is a motion sequence, whose process of creation can be discern through the brushstrokes. Enough of the big words, let me introduce the gremlin who wrote this little essay by the way of explaining her paintings. Clearly, this exhibition consists of three parts: the Bodhisattva series, some autumn landscapes of Sarah Lawrence College and the "mamak stall" series. My first year in New York, my first autumn, the insistent intensity of the leaves, deep viridian green, turning golden, red, purple, rich browns.......

I grew up in a former tin-mining little town of Klang, 15 miles away from the capital of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. It used to be a sleepy town of boiling hot days, balmy nights and tropical thunderstorms that left the drains running with cool water. As a hyperactive child, and much to my grandmother’s chagrin, I often played in the drains after a thunderstorm, waist up in muddy water.

In

the following paragraph, I will attempt to describe to the non-Malaysian

or the non-Singaporean the concept of the "mamak stall". The

"mamak" stall, to put it simply, is the watering-hole of

Malaysians, young and old. This unique concept of an outdoors cafe is

quite unlike any other. Essentially, the food served at a mamak stall is a hybrid of Indian and Malay cuisine, the most popular meals may

consist of "roti canai", "teh tarik", "chicken

tandoori", "naan" and is usually accompanied by a choice

selection of freshly cooked curries. The cooks are almost always Indian or

Malay men. A mamak stall are found any where, by the road, by the river,

in shop houses and commercial buildings, any place where there are Malaysians, so to

speak. On most weeknights and more so during the weekends, students throng

these "mamak stall" for the traditional glass of hot milk tea,

iced lime juice and to just chat with friends. These stalls are open till the

wee hours of the night and some stay open all night. "Mamak

stalls" are also choice breakfast places because they open very early

in the mornings to cater for the working people.

There

is nothing fancy or pretentious about the "mamak stall". Plain,

rickety tables, plastic stools, several open stoves, solid brass pots, a

cigarette counter and a few good, burly cooks are all that's needed to start

business under a rain tree by the river. Customers are frequent and with

dependable appetites and tastes. Most of the time, they ask for nothing

more than a piping hot glass of "teh tarik" and crisp "roti

canai" doused in fish curry. Mamak stall customers come from all

walks of life, from the coolie who has been hauling rice sacks all day to

the corporate executive who comes for his/her regular cuppa, college

students, high school students, everyone is of equal status sitting at a mamak

stall. The official dress code is an old T-shirt, some worn-outs and

sandals. Close one eye on the sometimes unsatisfactory hygiene, customer

satisfaction is hundred percent, evident by the mushrooming watering-holes

throughout Malaysia. And it's not even a franchise, not a MacDonald's, or

a Dunkin Donuts, or a Burger King. It is essentially a Malaysian way of

life.

There

is nothing fancy or pretentious about the "mamak stall". Plain,

rickety tables, plastic stools, several open stoves, solid brass pots, a

cigarette counter and a few good, burly cooks are all that's needed to start

business under a rain tree by the river. Customers are frequent and with

dependable appetites and tastes. Most of the time, they ask for nothing

more than a piping hot glass of "teh tarik" and crisp "roti

canai" doused in fish curry. Mamak stall customers come from all

walks of life, from the coolie who has been hauling rice sacks all day to

the corporate executive who comes for his/her regular cuppa, college

students, high school students, everyone is of equal status sitting at a mamak

stall. The official dress code is an old T-shirt, some worn-outs and

sandals. Close one eye on the sometimes unsatisfactory hygiene, customer

satisfaction is hundred percent, evident by the mushrooming watering-holes

throughout Malaysia. And it's not even a franchise, not a MacDonald's, or

a Dunkin Donuts, or a Burger King. It is essentially a Malaysian way of

life.

I

have a soft spot for the mamak stalls in my hometown of Klang. For it

defines the pace of my childhood and continues to do so until today; the

leisurely breakfasts with my mother after an early morning swim practice,

the after-class tea breaks with my college friends on balmy, rainy days in

Petaling Jaya, the late-night meals with my father who, during the summer

vacation, insisted that I eat at the mamak stall every night until the day

I left for Sarah Lawrence College. Takeouts from the mamak stall were a

regular feature during the World Cup in June this year. Better still, the

owners had television sets installed for customers to watch the soccer

matches while they chewed down slices of "naan" and fried

noodles.

I

have a soft spot for the mamak stalls in my hometown of Klang. For it

defines the pace of my childhood and continues to do so until today; the

leisurely breakfasts with my mother after an early morning swim practice,

the after-class tea breaks with my college friends on balmy, rainy days in

Petaling Jaya, the late-night meals with my father who, during the summer

vacation, insisted that I eat at the mamak stall every night until the day

I left for Sarah Lawrence College. Takeouts from the mamak stall were a

regular feature during the World Cup in June this year. Better still, the

owners had television sets installed for customers to watch the soccer

matches while they chewed down slices of "naan" and fried

noodles.

The paragraph that follows may be the gibberish spouted by a small-town bumpkin who landed in New York by chance and for no other reason than to study at a liberal arts college called Sarah Lawrence College. I spent the weekends running around New York City. I hopped into museums, bric-a-brac shops, flea markets and the eclectic collection of quaint art galleries in Soho. I traipsed into costume shops, secondhand bookstores and theatre boxes in Soho and Tribeca, never knowing what I might uncover next. The tall, solid brownstones in which many of these shops are housed in may seem formidable from the outside, but within are treasures galore. The city is vibrant and alive, pulsating energy and creativity, from the aspiring ballerina counting out change at the Upper West side corner store to the street dancers in Times Square to the tattoo artist at St Mark's Place. Everyone is immersed in the universal dance of creative expression, which is both momentous and timeless.

New

York City defies the gravity of reason, because it is always morphing,

moving, erupting. To put it simply, it has an amazing concentration of

cultures and artistic diversity; the mainstream arts existing

synergistically with those of experimental nature. There is always a niche

and space for experimental art in all its genres. To quote artist Ervin Earle:

New

York City defies the gravity of reason, because it is always morphing,

moving, erupting. To put it simply, it has an amazing concentration of

cultures and artistic diversity; the mainstream arts existing

synergistically with those of experimental nature. There is always a niche

and space for experimental art in all its genres. To quote artist Ervin Earle:

“Art is another word for life and life is infinite, beyond definition, beyond understanding even. Nothing said can contain but a drop of it. Art encompasses all aspects of existence. Life and truth and consciousness and color and sound and feeling. All are the same thing. Seeing we call it painting. Hearing we call it music. Reading we call it poetry, and living we call it life. So art is an attempt to capture life."

I loved the permanent exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum showcasing ancient Southeast Asian art because I was surprised at how much Southeast Asian treasures have traveled half-way around the globe to be exhibited in a Western location. I decided to base my independent project on creating watercolor and ink paintings based on bodhisattva sculptures at the Met Museum. During my first year in New York, I spent a ridiculous amount of time drawing the sculptures until the security guards knew me by name. I observed the graceful curves and long, flowing lines of these representation of the bodhisattvas who supposedly delayed their own enlightenment in order to bring salvation to mankind.

I created the bodhisattva series as a random response to the turmoil and devastation of September 11 last year when the World Trade Center in New York City was attacked. Being so far away from home, I felt the need to seek spiritual and emotional solace when humanity is thrown into turmoil. Having grown up with a Taoist-practicing grandmother and living in a multi-cultural country where religious practices co-exist and intermingle, bodhisattvas echoed the universal theme for peace. Life is like being an ant, you don't know when someone's thumb might show up and mash your little body to paste.

"...Bodhisattvas take on the suffering of all sentient beings, undertaking the journey to liberation not for their own good alone, but to help all others. And eventually, after the attainment of liberation, not dissolving into the Absolute or fleeing from Samara, but choosing instead to return again and again to devote their wisdom and compassion to the service of the world."

Peace of mind. Said the Dalai Lama, “in the final analysis, the hope of every person is simply peace of mind.” Peace of mind. Working on the bodhisattva series, I approached this subject from an artistic and aesthetic point of view rather than from a religious perspective, in the search for peace of mind. The idea is to express the universal value of peace from the Buddhist philosophy while addressing the issues of life and ways of the world. Peace.

LEE Hui Ling, September 29,2002